We All Live Downstream (of Waterbodies that are about to Get Dirtier)

3/29/2019

By Olivia Green and Alma Lowry

“Isolated” wetlands in the Chippewa Range in Wisconsin that may lose protection under the proposed rule|

(Photo from Wisconsin Wetlands Association wisconsinwetlands.org)

Hydrologically, it’s a fact: we are all connected through the hydrologic cycle. Some hydrologic pathways are straightforward—headwater streams feed into bigger creeks and rivers until they flow into the ocean. Some are complex—water disappearing and reappearing between the surface and subsurface several times before joining a permanent surface flow. These interconnections mean that damage done even to seemingly isolated waters can extend to major waterways. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is poised to ignore these facts in proposed new Clean Water Act (CWA) regulations, issued on February 14, 2019.

The goal of the CWA is to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.” 33 U. S. C. §1251(a). The CWA does this by prohibiting the discharge of pollutants into or filling in “waters of the United States” without a permit. But what are “waters of the United States” (WOTUS)? That definition is at the heart of the proposed regulatory changes.

Although the CWA may be seen as focused on larger, navigable waters like the Mississippi River, courts have long interpreted the CWA “as an all-encompassing program of water pollution regulation,” Milwaukee v. Illinois, 451 U.S. 304, 318 (1981), expressing “the evident breadth of congressional concern for protection of water quality and aquatic ecosystems” U.S. v. Riverside Bayview Homes, 474 U.S. 121, 133 (1985). Decades of research have shown that the integrity of our nation’s waters depends on the health of the entire system, including ephemeral and intermittent headwater streams and wetlands. The EPA’s proposed rule ignores basic science and congressional intent and defines WOTUS to eliminate:

ephemeral features (defined as flowing or pooling only in direct response to precipitation)

non-navigable, isolated lakes and ponds

wetlands not adjacent to a jurisdictional waterbody and lacking a direct hydrological surface connection to a jurisdictional waterbody in a typical year (“isolated wetlands”)

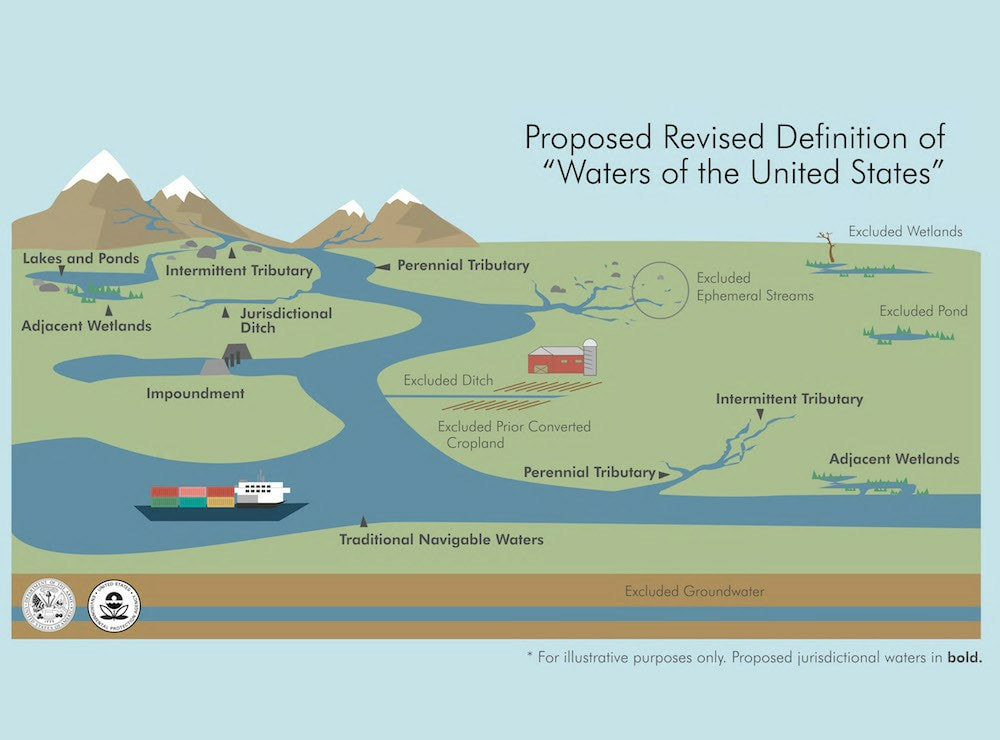

EPA’s illustration of the revised WOTUS definition. Note the illustration doesn’t show groundwater connections between “isolated” features and other waterbodies. In reality, such isolation is extremely rare.

The proposed changes will strip protections from more half of the waterways in this country and have enormous consequences. Ephemeral streams and ditches could become unregulated dumping grounds for pollutants, which then make their way into major water sources via seasonal flows or flooding. Construction or filling in ephemeral waterways may interfere with their seasonal role as recharge sources for perennial or intermittent waterways or as seasonal habitat.

The loss of wetlands protection is similarly critical. Truly isolated wetlands are extremely rare. Nearly all wetlands are places of preferential groundwater recharge and high degrees of surface and groundwater interaction. Even without obvious surface water connections, water from a wetland will eventually reach downstream navigable waters through subsurface flow. Under the proposed rule, pollutant discharges to isolated wetlands won’t be prohibited by the CWA and contaminants may flow through these underground pathways to groundwater and navigable surface waters.

The revised CWA rules would allow “isolated wetlands” to be filled in and destroyed with impunity. This could have dire ecological impacts on wildlife, such as salamanders and wood frogs, which depend on “isolated wetlands” and ephemeral ponds for breeding. This short-sighted exclusion also puts at risk important flood attenuation and water filtration protections that wetlands provide by interrupting the flow of stormwater runoff into lakes and streams, providing temporary storage of flood waters, and trapping some contaminants and nutrients in wetlands soils where toxins may degrade and excess nutrients may be used by plants. As Justice Kennedy observed, “it may be the absence of an interchange of waters prior to the dredge and fill activity that makes protection of the wetlands critical to the statutory scheme.” Rapanos v. U.S., 547 U.S. 715, 775 (2006) (Kennedy, J., concurring).

EPA’s own research recognizes the “connectivity” and potential importance of “isolated wetlands” and ephemeral streams. EPA’s 2015 “Connectivity Report,” which thoroughly reviewed the available science and was vetted by experts in the field, found that the research:

unequivocally demonstrates that streams, individually or cumulatively, exert a strong influence on the integrity of downstream waters. All tributary streams, including perennial, intermittent, and ephemeral streams, are physically, chemically, and biologically connected to downstream rivers via channels and associated alluvial deposits where water and other materials are concentrated, mixed, transformed, and transported. (at 6-1)

Even “isolated wetlands” were found to have potential connectivity, depending on location and time of year. Certainly, the science does not support excluding either type of water body from CWA regulation as unrelated to the “chemical, physical, and biological integrity of our Nation’s waters.”

EPA suggests that its decision to categorically exclude certain waters from the WOTUS definition is simply shifting regulatory authority to the states, arguing “that science cannot be used to draw the line between Federal and State waters.” 84 Fed. Reg. 4154, 4176 (Feb. 14, 2019). Because states can regulate more broadly under their own jurisdiction, EPA argues that ephemeral streams and isolated wetlands can still be protected by state law, but are simply outside the proper jurisdiction of federal law.

This argument is a fallacy. Downstream states will be powerless against the regulations, or lack of regulations, implemented by upstream neighbors. Pollution and floodwaters flow downstream. Unchecked development of wetlands in an upstream state could leave downstream states vulnerable to intensified flooding with no recourse. Similarly, degradation of critical habitat in ephemeral streams could affect downstream fisheries. In each case, downstream states’ only recourse is to set disproportionately higher standards in their state, putting them at an economic disadvantage. A uniform, federal scheme is necessary to ensure adequate water protection for all, with states free to set higher standards as desired.

How to Get Involved

ASLF is preparing comments on the proposed new rule, challenging EPA’s decision to exclude critically important ephemeral waters and inland wetlands from CWA protections. Please join us and many other environmental organizations in urging the EPA to rely on established science, not partisan politics, to set the appropriate scope of these regulations. More information is available on the EPA website. Draw from our suggested comments or write your own.

COMMENTS ARE DUE BY APRIL 15, 2019!

Remember, we all live downstream.